Soldiers

There were no permanent armies in Britain when the English Civil War started in 1642. The last time that the country had experienced anything close to a full scale war had been the threat of the Spanish Armada 70 years before. Every county had a local militia or ‘Trained Bands’ that could be called up in time of war, but many of these split between the different sides. As such, both Royalists and Parliamentarians had to ask for volunteers to fill their armies, though many noblemen who raised regiments forced their tenants and servants to join up. As the wars went on, both sides introduced conscription, which was extremely unpopular and many men deserted.

Some senior officers on both sides, such as Prince Rupert or Sir Thomas Fairfax, had gained prior military experience in the Thirty Years’ War on the Continent. Others figures such as Oliver Cromwell had little or no experience at the start of the war and had to learn by experience.

The Cromwell Museum displays examples of the sorts of equipment carried by soldiers during the English Civil War, some from our own collections and others kindly loaned to us by the Royal Armouries.

The Foot

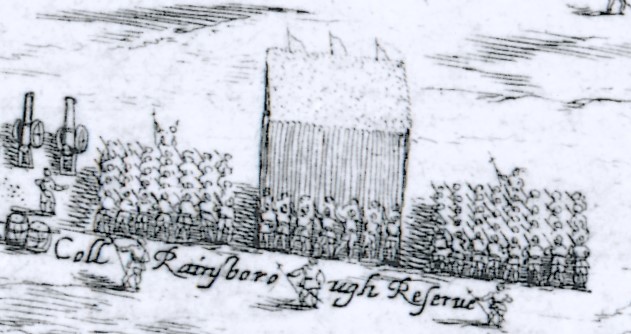

Infantrymen were organised in regiments commanded by a colonel, with each regiment sub-divided into ten or twelve companies of 100 men, each with its own flag or colour. In reality, with a lack of recruits, most regiments were between 400 – 600 men. In battle, each regiment would be formed up with a block of pikemen in the centre and equal bodies of musketeers on either flank.

Infantry regiments usually had two types of soldier: pikemen and musketeers. For most of the war there would be two musketeers for every pikeman, and by its end the New Model Army perhaps had a ratio of 3 or 4 musketeers to a pikeman.

At the beginning of the war many pikemen were equipped with armour, usually a back and breastplate and often thigh plates or ‘tassets’. As it was quite cumbersome, this was rapidly abandoned, and for much of the war most pikemen would have little more than a helmet to protect them. They were armed with a short sword for hand-to-hand fighting, and a pike, a spear 16 to 18 feet (4.7 – 5.5 metres) in length, made of ash with an iron spear head. They were formed into blocks of men that could present a forest of pikes to an opponent, ‘charged’ or levelled against the face against other infantry, or more importantly form a hedgehog of pikes or ‘schiltron’ which musketeers could crouch and shelter under to defend against a cavalry charge.

Musketeers were armed with a musket, a simple firearm around 4.5 feet (1.4 metres) in length which fired a lead musket ball weighing about 2/3 oz (18g) using a gunpowder charge. The musket most commonly used was the matchlock, which was fired by touching off a priming charge with a piece of burning slow-match cord. As the war went on the matchlock was increasingly replaced by the more reliable ‘firelock’ or flintlock musket, which used a piece of flint striking a steel in the mechanism to create sparks, igniting the priming charge.

A musket could hit and kill a person at up to 300 yards but was inaccurate at anything over 50 yards, hence musketeers being gathered together to fire in massed volleys to create a hail of lead that was bound to hit an opponent. At the beginning of the war many musketeers carried a forked stick or rest to help support the musket an aid accuracy, but these were soon abandoned. The musketeer carried his ammunition in a leather bandolier, often known as the ‘twelve apostles’ from which twelve wooden tubes hung, each containing enough gunpowder for a shot, as well as a powder flask and bag of bullets. The musketeer also carried a sword for personal defence, although the butt end of his musket was used as much and could be a very effective club!

Drummers accompanied each regiment, not just to inspire the troops with some martial music and provide a beat to march to, but to relay orders. In the noise of battle, it was often difficult to hear even shouted commands, so the ‘calls of war’ or distinct drum beats would signal the troops to attach, retreat, march etc.

The Horse

Cavalrymen were also organised into regiments, usually of six troops commanded by a captain, and numbering between 30 and 100 men. The ideal at the beginning of the war was to have some heavy cavalrymen or Cuirassiers, equipped in heavy armour similar to that of a medieval knight, which could act as shock troops in battle. In practice these soldiers were expensive to equip, so very few men and only a couple of full regiments were equipped this way throughout the whole war, most famously Sir Arthur Haselrig’s regiment in the Parliamentary forces, nicknamed his ‘Lobsters’.

Most civil war cavalry were equipped as a style of cavalry known as ‘harquebusiers’, as they carried a harquebus or carbine, although this was often only an ideal. They would always carry a pair of pistols – fired by a flintlock or wheel-lock mechanism – in holsters in front of their saddle, and a cavalry basket-hilted broadsword. We have examples of this type of sword in our Museum that were used by Cromwell himself. Cavalrymen would be protected by a thick buff-leather coat that could turn a sword cut, and/or a back and breastplate. They would usually wear a helmet, often of the distinctive ‘lobster pot’ type.

Dragoons were mounted infantrymen who rode small horses or cobs to move into position and then fought on foot. They wore no armour and usually carried a musket or carbine and sword. They could protect the flanks or scout ahead of an army.

Artillery

Cannons were becoming increasingly widespread during this period, with most guns being muzzle-loading, smooth bore, and cast in bronze or iron. Heavy guns were used for battering down walls in sieges. Mortars were often used to fire explosive shells over the walls of an enemy position.

Armies were usually well-equipped with field artillery. The heavier field guns were set up at the beginning of a battle and would not move thereafter, firing on the enemy army from long range. Smaller cannon would accompany the infantry, being used to cover the gaps between infantry units. The guns could be moved with the infantry as it advanced to bolster the firepower of the musketeers.

Cannon could cause significant damage – an iron cannon ball could take out an entire file of soldiers, whilst ‘canister shot’ (an iron tin filled with scraps of metal and iron nails) fired from a cannon at close range could cause horrific injuries.

Cavaliers vs. Roundheads?

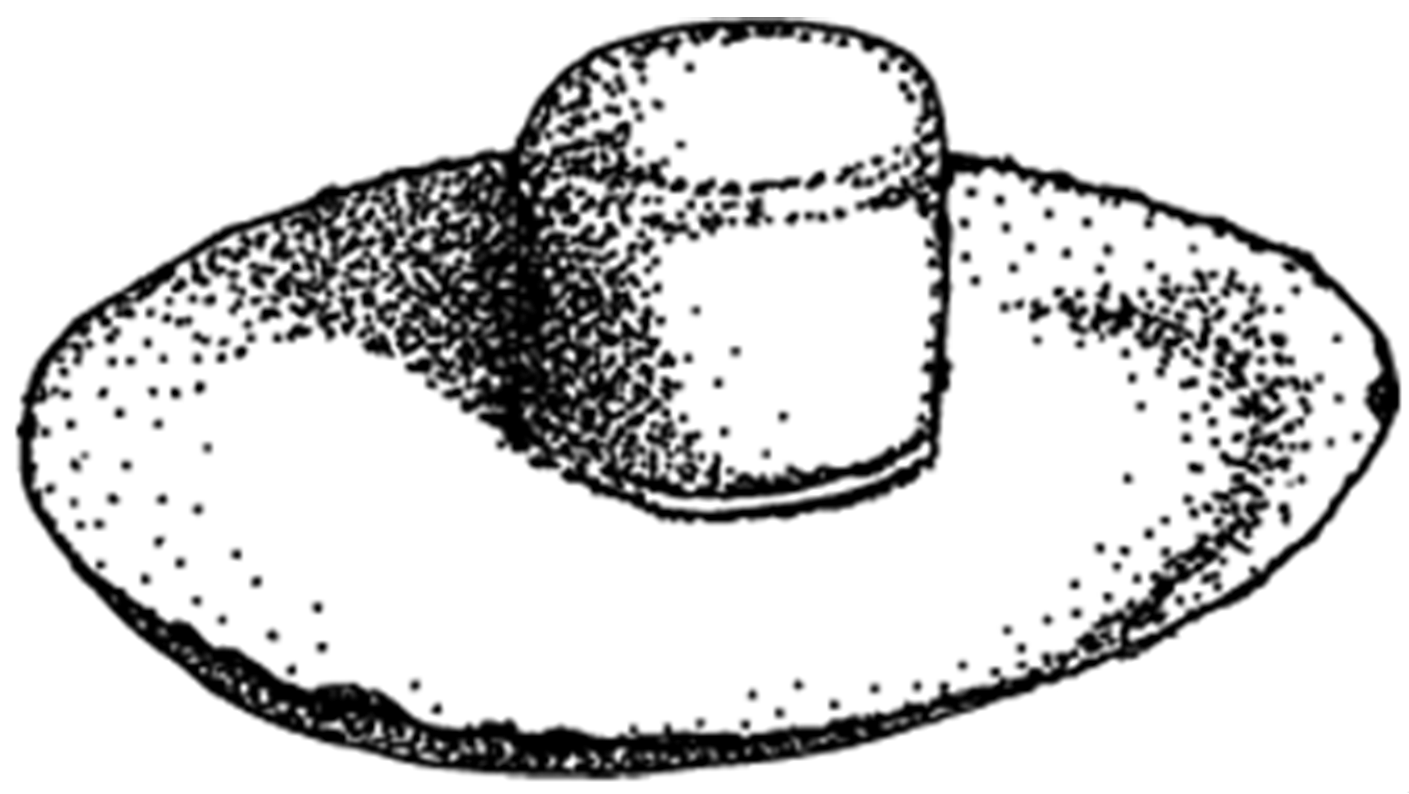

The popular image of the Civil War is of Royalists in floppy hats, lace and feathers, against Parliamentarians in lobster pot helmets and buff coats. The reality was very different to this myth, which was propagated by the Victorians.

In reality, fashionable clothing and long hair would have been worn by wealthy men on both sides, particularly officers. The buff coat and lobster pot helmets were standard equipment for cavalrymen in either army. There was little uniformity in equipment that was issued, regiments wore uniform coats at the taste of the colonel who paid for them, and it was very difficult to tell the two sides apart. As such, there are many recorded examples of what today we would call ‘friendly fire incidents’ when men accidentally killed others on their own side by accident. To help try and distinguish between them, officers wore coloured sashes – tawny orange or pale blue for Parliamentarian, crimson red for Royalists. Men might wear a ‘field sign’ for a particular battle to show which side they were on – examples include a white rag tied around their arm, a scrap of paper or sprig of greenery tucked in their hat.

This did change with the advent of the New Model Army. For the first time it was decided to equip the whole army in a single coat colour (with variations in cuff colours for different regiments). As it was cheap and a large quantity of it was available, red woollen cloth was used. This has remained a tradition for the British Army ever since, and red coats are still worn as the dress uniform of many regiments today, some of which are derived from New Model Army regiments.

The Battle of Marston Moor – a mid 19th century painting by James Ward

Detail from the Battle of Naseby plan showing an infantry regiment

Engraving of a Pikeman by Jacob de Gheyn, 1607

Musket balls from the site of the skirmish near Grantham, 1643

Engraving of a Musketeer by Jacob de Gheyn, 1607

Woodcut of a Cuirassier by John Cruso, 1632

Cannonball from the battlefield at Marston Moor