Causes of the Civil War

Although there is general agreement between historians as to the different causes of the Civil War, there is a good deal of debate as to how much emphasis or importance to each of them. There were several factors which led to the country being plunged into a bloody conflict; many political, some religious, others personal or local in nature.

Religious divisions played a role, triggering conflict in Scotland and Ireland and providing a background of suspicion and distrust between groups in England. The Reformation and religious changes in the 16th century under the Tudors had led to a Protestant Church of England, albeit with a level of ritual and tradition retained in many services. This left the surviving Catholic minority feeling dissatisfied and persecuted, an expression of which was the attempted ‘Gunpowder Plot’ in 1605 to assassinate King James I and his Parliament.

As a result, Catholics were viewed with deep suspicion and fear, not least as continental Europe had been torn apart by the bloody Thirty Years’ War (1618-48) between Catholic and Protestant powers. At the other end of the religious divide, some people felt that the Reformation had not gone far enough and wanted the church to be more Protestant.

These people collectively acquired the nickname of ‘Puritans’. Scotland was similarly divided, with the dominant church in the southern half of the country and cities being strict Calvinist Protestant, whilst many in the highlands and north of the country retained the Catholic faith. In Ireland most people were Catholic, but since the Elizabethan period a substantial minority of Scots and English Protestant settlers had been become dominant in the northern Ulster counties.

‘Divine Right’

Politically the war was a struggle over how much power parliament should have over the monarchy, challenging the notion that an English monarch had the right to rule without the consent of their people. Up to this point England had been governed by an uneasy alliance between the monarchy and parliament. The role of parliament had been developing since the its inception in the middle of the 13th century and by the 1600s had acquired widely accepted powers which meant it could not easily be ignored by the monarch. The most important of these was parliament’s ability to raise taxes, authorising any changes or extensions to existing taxation as it represented the people who would ultimately pay them.

The political and religious status quo began to become unstable with the accession of Charles I in 1625. Like his father James I before him, Charles believed he had the God-given ‘Divine Right’ to rule, but where James had largely worked with Parliament, Charles’ decisions from the outset of his reign antagonised Parliament, from his choice of political advisers, his involvement in expensive foreign wars, to his marriage to a French Catholic princess. Parliament responded in 1628 by forcing the king to agree to ratify the ‘Petition of Right’, a document that outlined specific personal and parliamentary liberties that the king could not infringe. Tensions between the two continued to escalate, until Charles dismissed Parliament in 1628 and would rule without it for the next eleven years.

Taxation without Representation?

During his ‘Personal Rule’, Charles used legal loopholes to squeeze money out of his subjects, such as fining those who had failed to attend his coronation and who had been eligible for a knighthood and selling title and honours. He also exploited taxes that had not been used for some time, such as Ship Money, a levy which had been used by tradition on coastal counties to help pay for the upkeep of the Royal Navy. Charles levied it on inland counties by 1635, which many felt was unfair. Prominent gentlemen such as John Hampden refused to pay on principle and were taken to court as a result; although the courts found in the king’s favour, the controversy was such that he was forced to reverse his policy.

A Matter of Faith

Charles’ religious policies also antagonised many. In 1633 he appointed William Laud as Archbishop of Canterbury, a man who shared Charles’ religious views and taste for ‘high church worship’, with the reintroduction of much ritual and ceremony into church services this included a new ‘Book of Common Prayer’ and alterations to church architecture, such as altar rails separating the clergy from the congregation. To many, particularly Puritans, this smacked of Catholicism and many began to fear that Charles meant to reintroduce the ‘old religion’.

Conflict flared up after 1637 when Charles attempted to extend his religious reforms to Scotland – at this time a separate country of which he was also king. Riots broke out in Edinburgh the first time that the ‘Book of Common Prayer’ was used. The following year the Scots objections to royal policy were put down as part of a document the ‘National Covenant’, signed by large portions of the population where they swore to maintain their existing religion against Charles’ reforms. By 1639 this had become open warfare in the first of the ‘Bishop’s Wars’ as Charles gathered an army to try and enforce his will. A brief attempt at peace with the declaration of Berwick failed, and the second Bishop’s War in 1640 resulted in a Scots army crossing the border, which lead to the defeat of the English army at the Battle of Newburn and seizing the important port of Newcastle.

Facing open rebellion in Scotland, Charles found himself in desperate need of money and had no option but to summon parliament. Parliament immediately took this as an opportunity to discuss its grievances with the king, but only lasted three weeks before Charles shut it down again, thus becoming known as the “Short Parliament”. The crisis and conflict with Scotland wouldn’t go away and six months later Charles bowed to pressure and once again summoned parliament. This time around parliament proved even more hostile with MPs and members of the House of Lords seeing their chance to demand radical reform.

King vs. Parliament

Over the next 18 months Parliament passed a multitude of laws cutting back Charles’ power, including giving MPs power over the king’s ministers, making sure Parliament had to approve any changes to taxation, that Parliament had to be called at least every three years, and the King was forbidden from dissolving parliament without its consent. They also impeached Charles’ chief advisor Thomas Wentworth, (Lord Strafford), and had him executed.

In 1641 Irish Catholics rose against English rule and the plantation of Protestant settlers. Newsbooks published in London fanned fears of Catholic invasion with exaggerated stories of tens of thousands of Protestants being massacred. Rumours circulated that the king was sympathetic to the rebels and many in Parliament feared that any army raised to quell the rebellion might be used against them instead.

The crisis came to a head on January 4th 1642. King Charles marched into Parliament with an armed guard and demanded that the House of Commons hand over the five MPs who were his biggest critics: John Pym, John Hampden, William Strode, Denzil Holles and Sir Arthur Haselrig. Tipped off in advance as to the king’s intentions, none of the MPs concerned were present. Charles bitterly observed that the “birds were flown” and left. Days later Charles left London for the north of the country. Negotiations continued but both sides were becoming increasingly polarised.

Communities started to take sides – the port of Hull for example refused entry to King Charles and declared its support for Parliament. Local loyalties and rivalries played a part in which side people took. In Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire many people objected to the drainage of the Fens being undertaken on behalf of wealthy investors licensed by the King, as it threatened their traditional trades and way of life. As such they sided with Parliament and many of these ‘Fenmen’ would join Cromwell’s regiment of horse.

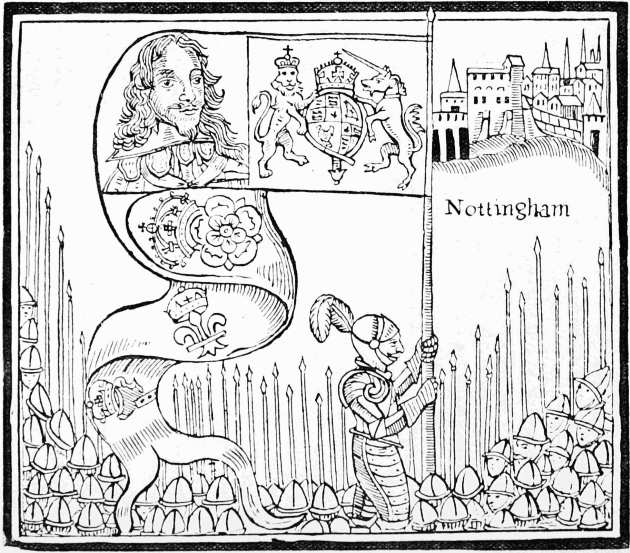

Six months later, on 22 August, the King raised his royal standard in Nottingham, declaring war on his own Parliament. The First Civil War had begun.

What’s in a Name?

Today we tend to still use the nicknames for the two sides during the Civil War that were created at the time. Those who were supporters of the monarchy, the Royalists were called ‘Cavaliers’; those who were Parliamentarians were nicknamed ‘Roundheads’.

What many people don’t realise is that these nicknames were originally insults. One of the centres of Parliamentarian support was London, where teenage apprentices often had their hair cut short (like most modern hairstyles) at a time when it was fashionable for men to have shoulder length hair. By calling the Parliamentarians ‘Roundheads’ the Royalists were implying that they were no more than an unruly bunch of silly boys.

By contrast, the Parliamentarians called the Royalists ‘Cavaliers’, a word derived from the French or Spanish words for a horseman. By this they were insinuating that they might be Catholic, or that they were associated with England’s traditional enemies.

Whilst the Cavaliers adopted their nickname, almost as a badge of pride, the Parliamentarians saw the word Roundhead as the insult that it was designed to be. A soldier in the Parliamentary army who called one of his fellow soldiers ‘Roundhead’ could find himself being severely punished.

Woodcut illustration of the raising of the King’s standard at Nottingham on 22 August 1642

Portrait of King Charles I (1600 – 1649), circle of Sir Peter Lely

Engraving of John Hampden MP (1594 – 1643)

A puritan preacher (thought to be Hugh Peters) preaching

Engraving of John Pym (1584 – 1643)

Woodcut from a Civil War newsbook, depicting the quarrel between Roundheads and Cavaliers